My Unweek

Sunday, November 25, 2012

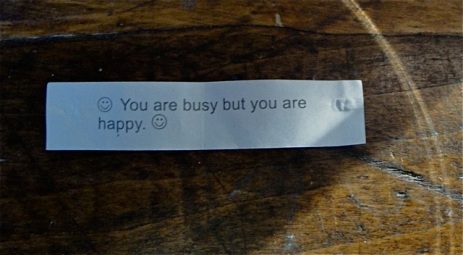

Well, the fortune got the first part right at least.

I am trying very hard to wrest control of my life back from the forces of chaos that seized it months ago.

Through sheer stroke of luck, I ended up with a completely unscheduled week this week, and immediately became committed to keeping it that way, to not scheduling anything, just keeping it open. I was very excited about this prospect, but then with the week at hand, started to worry about the best way to spend it. Catch up on my work? Work on the house? See if I remember how to use a cookbook?

So many options!

I was having trouble figuring out what to do, and worrying that I would squander this precious resource. Ultimately, I decided I needed to think about it as an Unweek.

An unweek?

Let me explain.

In the tech world, there is something called an Unconference.

An unconference is basically a conference with no set agenda for sessions. So instead of having everything mapped out, this “expert” talking about this topic at eleven o’clock in the Tulip Room, you get a bunch of people together and the first session is people pitching topics. You can make a pitch for something you want to present, or you can make a pitch for something you want to learn about. All of the potential topics get written on post-it notes and then things get combined and written on a whiteboard and assigned to times and rooms and off everyone goes.

I’ve been to two unconferences and I’m now completely sold on the idea.

The person who has run the unconferences I’ve been to is our local tech guru/social media superstar Ruby Sinreich (who, in 2007, got a flat tire on her way to a presentation she was scheduled to give and used Twitter to get a ride to the meeting — I tried to tell that story for more than a year before I was able to tell it without first having to explain what Twitter was and why anyone would use it). Ruby has given the intro to the unconferences I’ve been to and explained how it works. She says there are two rules for an unconference:

Rule #1: Whoever is here is the right group of people to be here.

Rule #2: If a session isn’t working for you — if you are not learning from it or contributing to it — it is your duty as an unconference participant to leave and go to a different session.

So I decided that I need to apply those rules to this week.

Whatever I think of to do is what I’m supposed to be doing. And if what I decide to do turns out to be not so good, I need to go do something else.

So that’s what I’m doing.

In other news…

(1) I am working on an Eating Down the Fridge project to close out the year. I got a new refrigerator in August, and the freezer is completely different from my old refrigerator, and smaller, and I can’t find anything anymore because the previous system I had doesn’t work with the new setup so I end up putting everything I take out anywhere it fits just so I can just close the door and get on with my life.

I’m working on getting rid of everything in my freezer (and also my pantry, just for good measure) and starting over with a blank slate and maybe figure out a new system that I can keep track of.

(2) I have grand plans for a series of “how to shop” posts that will outline my strategy for shopping and eating for approximately $100 a month. I have been hoping to get to this for a long time, and in October had a conversation with someone I’m friendly with who said she really wants to see it, she really needs it, she needs help. So I promised her I would get to it and put it up and let her know when it was done. And I will. Soon.

In the meantime, those of you who are interested and have not yet read it can check out the links to the Hundred a Month project linked in the sidebar. That’s not exactly a how-to, but it does outline a month of shopping and eating for approximately $100 a month that I wrote about in 2010. And some of the posts are kind of funny.

(Note that the best way to navigate through that project is to use the calendar in the sidebar. If you start with the post linked in this paragraph, you’ll be on January 7, 2010, and you can click the blue numbers in the calendar to get to the next post.)

(3) I went to the library the other day looking for a Dave Ramsey book, because he gets referenced a lot but I’ve never read anything of his, but unfortunately everything was already out. But I noted that his book was published by Thomas Nelson, which is a Christian publisher, and that reminded me of America’s Cheapest Family, by Steve and Annette Economides, who also have some Christian publishing link (though I can’t remember what that is right now, if it was their original publisher or their agent or exactly what the link was, I just remember noting it when I was researching them earlier in the year) and that reminded me that I started writing a review of their books that I never finished and posted.

So that will be coming soon, since it’s actually mostly written. I just need to review and make sure everything I wrote makes sense and isn’t likely to offend anyone and then put up.

And that’s what’s going on here.

Hope everyone has a good week. Or unweek, as the case may be.

In the Name of Ambidextrous Gluttony

Sunday, November 11, 2012

A while ago — a few years ago now — a friend gave me a copy of How to Travel with a Salmon, a book of essays by Umberto Eco. I had read The Name of the Rose many years before and didn’t love it, so I might have been inclined to turn down the offer of this book, but my friend said it was really good, she thought I’d like it, I should take it.

So I took it and I started it and would read it occasionally and some of the essays are very good and some are good but very dated (most were written in the mid- to late-1980s, and many of them deal with various forms of technology, so you can imagine how those read now) and some are parodies of things I don’t get at all so I just skipped those.

Last week I was visiting the friend who had loaned me the book and was thinking I should try to wrap it up and return it to her while I was there, even though I think she probably doesn’t care much whether she gets the book back since she’s reading everything on her iPad these days. But regardless, it seemed like a good idea to finish it, so I was reading it on the bus, and the essay I happened to have been in the middle of the last time I was reading it on the bus (it’s a good bus-reading book, the chapters are all short and self-contained) is called How to Eat Ice Cream.

And as I opened the book and continued with this essay, I realized that it was about consumerism. And that it was brilliant.

Eco tells the story of his childhood in the 1930s in the Italian Piedmont, where street vendors would sell ice cream in two forms: a 2-cent cone or a 4-cent pie. He was allowed to get either the 4-cent pie or the 2-cent cone. However he says that he was fascinated by some of his peers whose parents bought them two two-cent cones.

These privileged children advanced proudly with one cone in their right hand and one in their left; and expertly moving their head from side to side, they licked first one, then the other. This liturgy seemed to me so sumptuously enviable, that many times I asked to be allowed to celebrate it. In vain. My elders were inflexible: a four-cent ice, yes; but two two-cent ones, absolutely no.

At the time, he couldn’t understand their refusal, and as he points out, “neither mathematics nor economics nor dietetics” justified it.

The pathetic, and obviously mendacious justification was that a boy concerned with turning his eyes from one cone to the other was more inclined to stumble over stones, steps, or cracks in the pavement. I dimly sensed that there was another secret justification, cruelly pedagogical, but I was unable to grasp it.

He then goes on to discuss what he has come to realize was the real reason.

Today, citizen and victim of a consumer society, a civilization of excess and waste (which the society of the thirties was not), I realize that those dear and now departed elders were right. Two two-cent cones instead of one at four cents did not signify squandering, economically speaking, but symbolically they surely did. It was for this precise reason, that I yearned for them: because two ice creams suggested excess. And this was precisely why they were denied me: because they looked indecent, an insult to poverty, a display of fictitious privilege, a boast of wealth. Only spoiled children ate two cones at once, those children who in fairy tales were rightly punished, as Pinocchio was when he rejected the skin and the stalk. And parents who encouraged this weakness, appropriate to little parvenues, were bringing up their children in the foolish theatre of “I’d like to but I can’t.” They were preparing them to turn up at tourist-class check-in with a fake Gucci bag bought from a street peddler on the beach at Rimini.

Nowadays the moralist risks seeming at odds with morality, in a world where the consumer civilization now wants even adults to be spoiled, and promises them always something more, from the wristwatch in the box of detergent to the bonus bangle sheathed with the magazine it accompanies, in a plastic envelope. Like the parents of those ambidextrous gluttons I so envied, the consumer civilization pretends to give more, but actually gives, for four cents, what is worth four cents. You will throw away the old transistor radio to purchase the new one, that boasts an alarm clock as well, but some inexplicable defect in the mechanism will guarantee that the radio lasts only a year. The new cheap car will have leather seats, double side mirrors adjustable from inside, and a paneled dashboard, but it will not last nearly so long as the glorious old Fiat 500, which, even when it broke down, could be started again with a kick.

The morality of the old days made Spartans of us all, while today’s morality wants us all to be Sybarites.

How to Eat Ice Cream was written in 1989, and I would argue that we’ve moved from the morality wanting us all to be Sybarites to the morality insisting that there is something wrong with us if we are not. It feels like “ambidextrous gluttony” is no longer the exception but the rule. You will never have to explain why you want something — a new computer, phone, television, car — but you often have to explain why you don’t.

Oh, for the days when the Italian grannies were in charge.